Summary

Stephan Gandhi Jones was born on June 1, 1959 to parents Jim and Marceline Jones, the only natural-born son in the otherwise adopted family (Reiterman 63). He grew up in Indiana, then eventually moved with the Peoples Temple to Ukiah, California. At 17 he was a defection risk, so his father Jim Jones sent him to work on the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project in Guyana, which Stephan loved in its early days (Reiterman 311). When his mother eventually moved to Jonestown, he bonded with her over their anger toward Jim Jones (Reiterman 401).

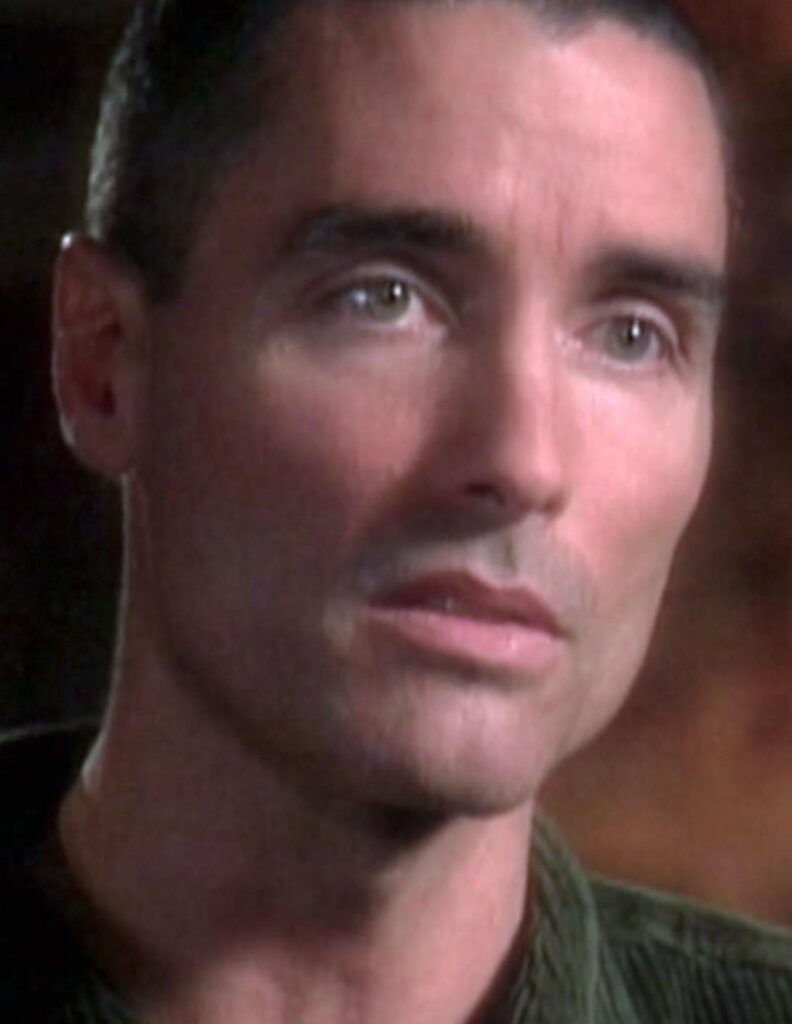

Stephan Jones eventually helped to form the Temple basketball team, and was away with them during the final White Night on November 18, 1978, allowing him to survive (Reiterman 474). He was 19 years old at the time. After being released from his three-month stay in a Guyanese prison, he moved back to San Francisco, where he stayed in close contact with other temple members (Gorney). Eventually he married and had three children (IMDb), and as of 2022 he continues to be active in education around Jonestown, writing articles and contributing to multiple documentaries. As of December 2022, Stephan Jones is 63 years old.

Early Life

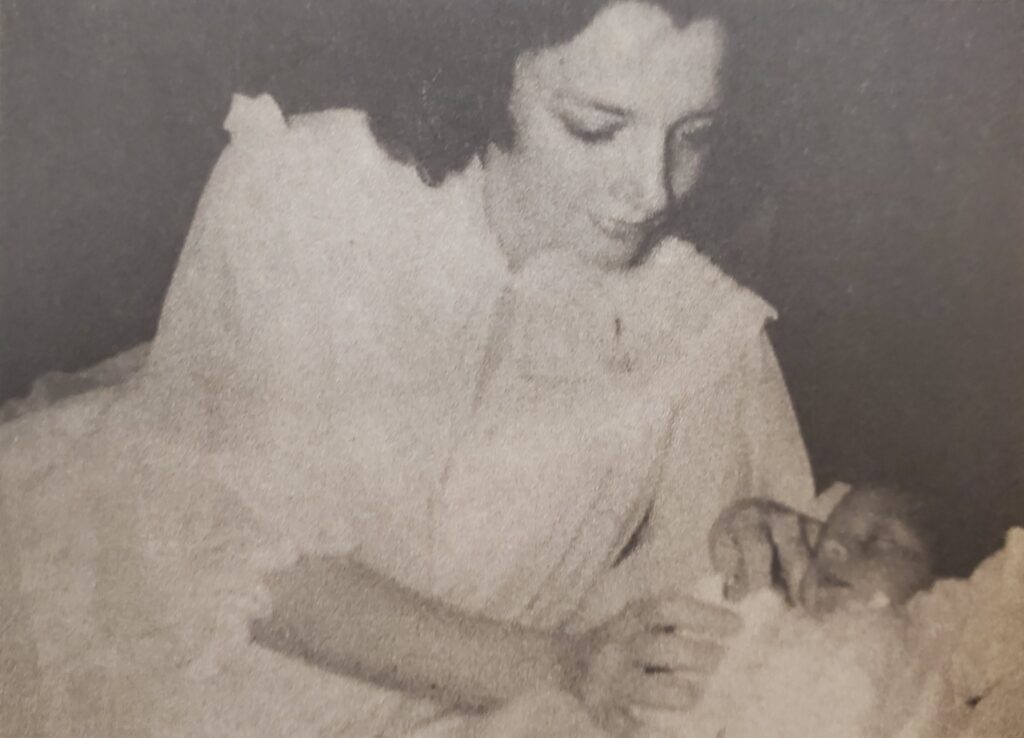

Stephan Gandhi Jones was born on June 1, 1959 to parents Jim and Marceline Jones in Indiana. Prior to Stephan’s birth, Jim and Marceline had adopted two children from Korea: a four-year-old named Stephanie and a two-year-old renamed Lew Eric. However, approximately a month before Stephan’s birth, Stephanie passed away in a car accident. After Stephan’s birth, the Jones family adopted two more children, another Korean child renamed Suzanne, and a black baby named James Warren Jones Jr. The Jones’ “rainbow family” acted as a symbol of racial integration within the temple community (Reiterman 63).

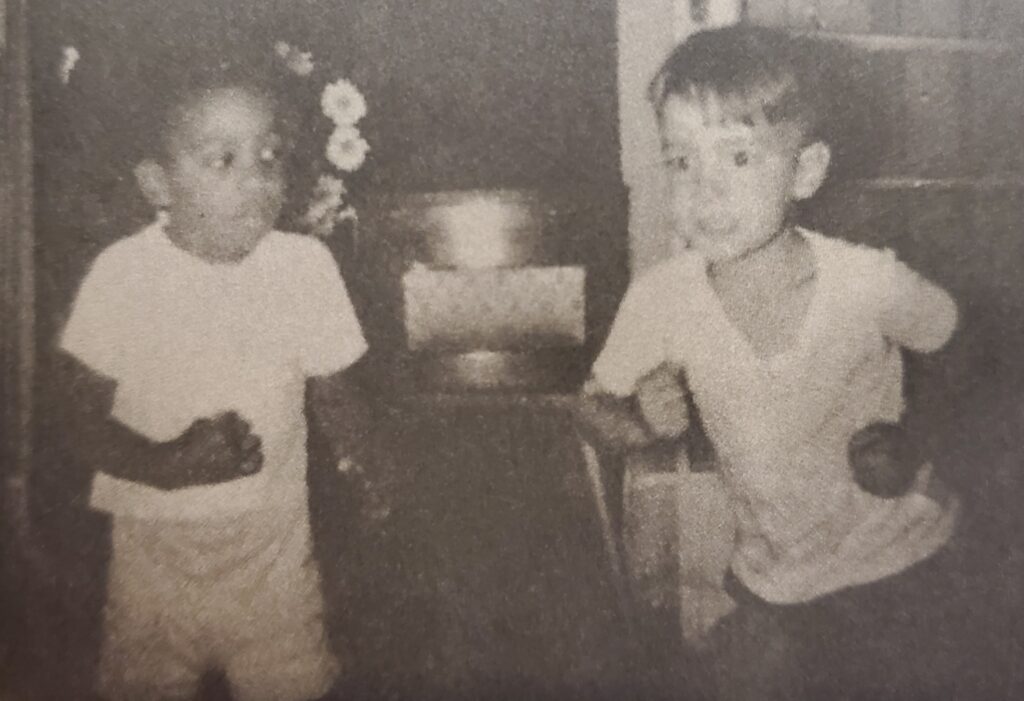

Top left: Marceline and baby Stephan. Top right: Young Jimmy and Stephan. Photos courtesy of Stephan Jones, acquired via Reiterman 134.

Stephan grew up in a high-stress environment as the People’s Temple grew and gained media attention (Reiterman 72). After the move to the idyllic Redwood Valley, California, things may have relaxed for a while. The atmosphere was described as secure and homey, with family meals and plenty of time outside swimming, picnicking, and playing football with other Temple kids (despite Jim Jones’ anti-sport rhetoric [Reiterman 102]). One day, at Stephan’s preferred Lake Mendocino, the Jones family took chase after some teenagers that had been stoning waterfowl. Stephan was proud when Jones caught one boy, shook him furiously, and lectured him (Reiterman 103).

Over time, a sibling rivalry developed between Stephan and his siblings, as Stephan was the only one who had been naturally-born from their parents. Stephan believed that church members preferred Jimmy (James Jones Jr.) over him, which sometimes resulted in teasing and fights between the two (Reiterman 104). Later, when they attended public school in Ukiah, Stephan and his siblings would fight at home but band together in public, with Stephan sometimes getting physically violent with other students in his defense of his siblings (who were sometimes attacked with racialized hate-speech)(Reiterman 181).

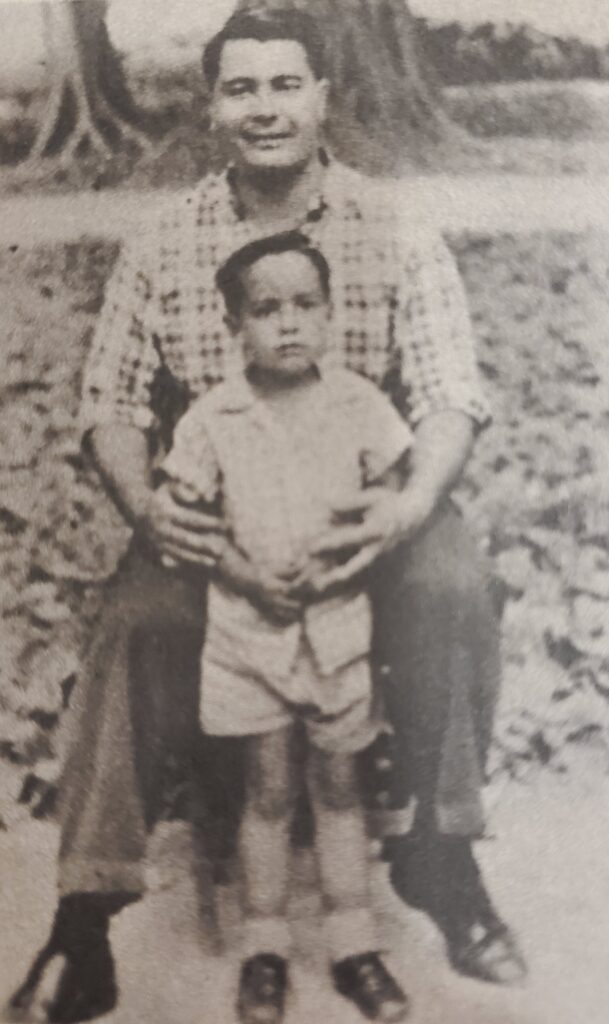

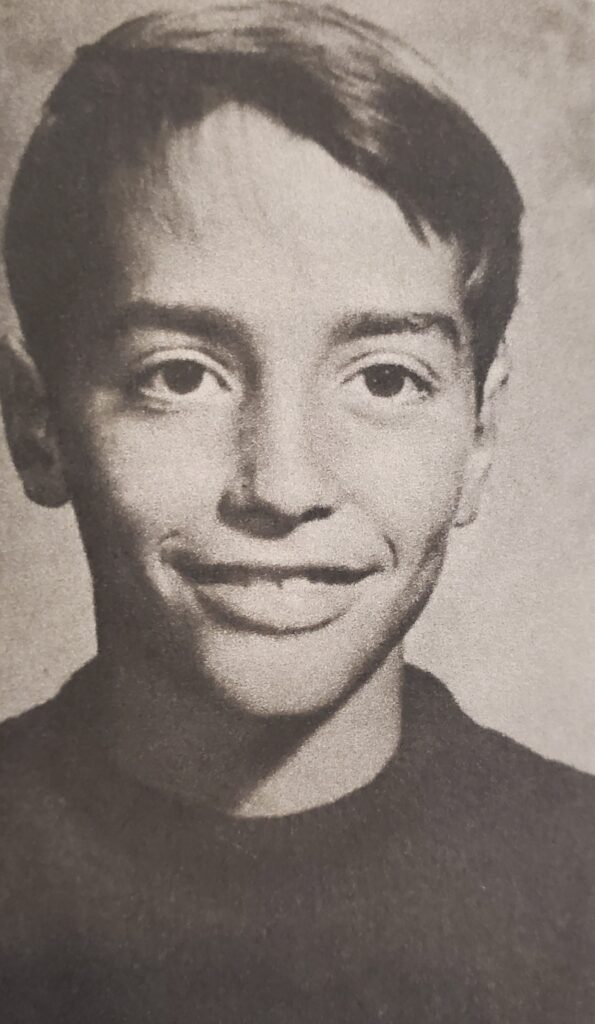

Top left: Stephan with his father, Jim Jones. Top right: Stephan Jones in Junior High. Photos courtesy of Stephan Jones, acquired from Reiterman 134.

Stephan Jones’ childhood was spent in the community of the People’s Temple, which had both benefits and drawbacks. It made it easy to find playmates, but there were also high expectations put on his shoulders as the son of the “prophet”. Stephan resented the attention other Temple children sometimes demanded of Jones, and would remind them in no uncertain terms that Jones was his father, not theirs (Reiterman 105).

In Ukiah, Stephan tired of the repetitive, high-energy Temple sessions and would sometimes sneak out with his friends and brothers. That was not always possible, however, and Stephan was eventually given the duty of carrying the microphone around during services and holding it for people making a testimonial or asking questions(Reiterman 106). Stephan’s dislike of the church services only grew stronger as he became privy to more of the Temple secrets, and was aware at a young age of the many things that were told to be truths, but were actually manipulations by Jones (Reiterman 106).

Stephan’s relationship with his father fluctuated between feeling intense positives and negatives. There were times when Jones reassured Stephan, or convinced him that they were a special pair. Stephan believed, for a time, that his father was a great man, and that they were so similar they may have had a telepathic connection (Reiterman 120). On the other hand, Stephan was sometimes hurt by his father not making time for his family (Reiterman 120), and felt his mother’s betrayal when he first learned of Jones’ extramarital affairs (Reiterman 121). This led to disillusionment and hostility toward his father, and a strong bond with his mother Marceline (Reiterman 124). This attitude continued into adulthood, and only intensified when in Jonestown.

Stephan’s high school experience was marked by grueling weekend temple trips, multiple switches in schools, difficulty making friends outside of the temple, and sports (Reiterman 309). Stephan was extremely passionate about athletics, participating in track, football, and baseball (Reiterman 181), with his true passion being for basketball, to Jones’ chagrin (Reiterman 308).

Stephan Jones made two suicide attempts as a high schooler. After the latter one he was sent to a psychiatrist in disguise, since Jones didn’t want anyone to know that his son needed mental counseling. The sessions were short-lived, especially since Stephan was not allowed to speak about his father during them (Reiterman 310).

Jonestown

When he was seventeen. Stephan got his own apartment, with the help of his mother and at the opposition of his father (Reiterman 310). Soon after, in December 1976, Jones requested that Stephan go to start working in Jonestown, possibly afraid that he was at risk of defecting (Reiterman 311). Stephan and Marceline both argued against it, but eventually both gave in and Stephan went at his mother’s request, agreeing to go for only a week, though as soon as he arrived in Jonestown he was informed that his position would be permanent (Reiterman 310).

The Jonestown settlers worked hard, sometimes until 11:00 pm (Reiterman 312). Despite there only being around 50 settlers, construction was quickly getting under way. Stephan soon found himself loving Jonestown, benefitting from the hard physical labor and intense comradery amongst early settlers (Reiterman 312). Stephan missed his mother, but was happier than he’d ever been. This time in Stephan’s life was marked with pride, enthusiasm, and community.

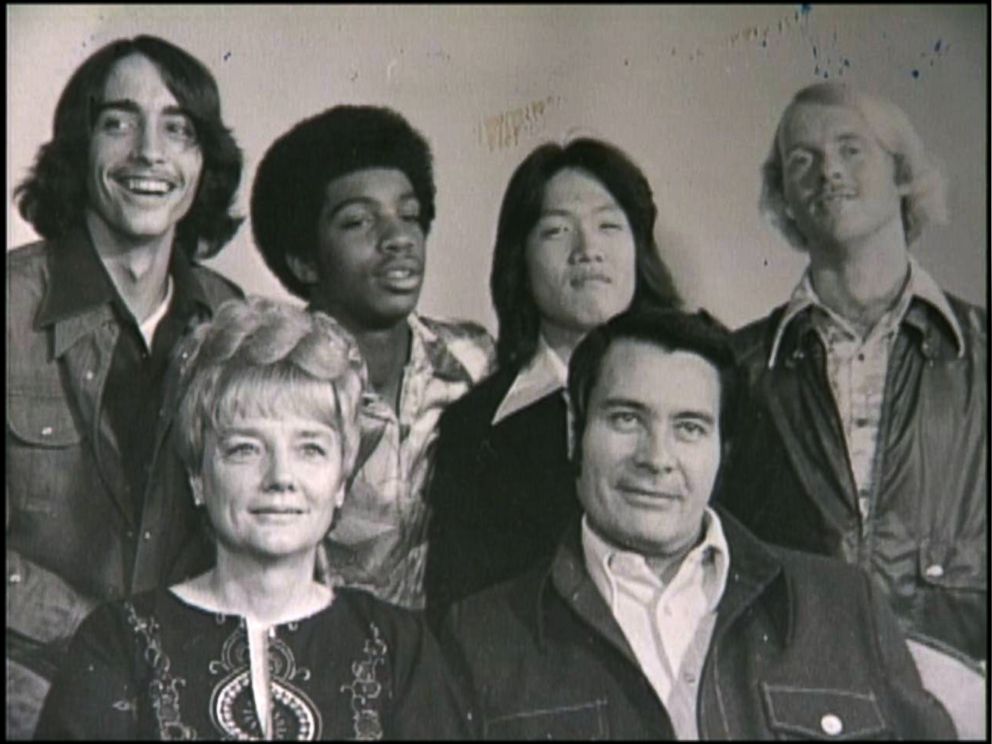

Jim Jones (top middle) with the early Jonestown settlers in 1974. Photo from Peoples Temple files, acquired from Reiterman 393.

In the summer of 1977 a large contingent of Peoples Temple members moved to Jonestown, growing the population from around 50 to over 1,000 over the course of a month (Reiterman 337). Some of the original settlers, included Stephan, resented the new arrivals who second-guessed their work (Reiterman 348).

September 5, 1977, Stephan learned there were guns in Jonestown when Jones used a .357 magnum revolver to fire a few shots at a banana leaf. As Stephan Jones and a few others were walking away, they heard a gunshot and raced back to Jones’ hut, where they found him on the floor in shock, but unharmed. Jones claimed that someone had tried to snipe at him through the window, but that a premonition led him to duck just in time. Stephan felt that the attack was real, though he knew his father wasn’t above staging such episodes (Reiterman 361). This “sniper attack”, plus the escalating political battle over John Victor Stoen, escalated into a full-blown crisis with the entire community being put on lock-down in preparation for an attack, possibly by mercenaries backed by Tim Stoen (Reiterman 362). By September 8, Stephan was questioning the validity of the crisis, and made a game out of surprising people on the Temple trucks. At one point, Stephan was alerted that someone may have tried to shoot Jones again, though when he investigated Stephan suspected the shots had come from someone standing within Jonestown, not in the jungle (Reiterman 364).

Jones often tried to involve Stephan in his various deceptions, including one in which Stephan would pretend to be shot while going to greet a lawyer from the U.S. (Reiterman 375), and one in which Stephan would pretend to kidnap John Stoen in a bag and then pretend to rescue him from his assailant (Reiterman 398). Stephan always argued against these plans.

By the end of 1977, Stephan was getting more fed-up with his father. One day, in response to Jones speaking over the loudspeaker, Stephan snapped, “Oh, fuck. That lying son of a bitch. Who wants to hear that shit?” The friend he’d said that to, Mike Touchette, reported his irreverence to Jones. Later, Touchette also reported to Jones that Stephan and Marceline commiserated about him (Reiterman 399).

By early 1978, Marceline was traveling back and forth between San Francisco and Jonestown, where she lived in her own private cottage near the center of the compound. Stephan spent many hours visiting with her whenever he got the chance (Reiterman 400). Marceline often confided to him about Jones and her anger toward him (Reiterman 401).

Stephan understood the White Nights to be tools of manipulation, and found them incredibly unpleasant (Reiterman 390). During a White Night in Spring 1978, he urged his father to stop, whispering, “You’re putting people through unnecessary pain” (Reiterman 391). Before the White Night of May 13, 1978 (Jones’ 47th birthday), Stephan argued against his father’s plans to shoot everyone in Jonestown, saying, “Do you really think you can take the lives of a thousand people? It’s not that easy” (Reiterman 405). At another White Night in spring or summer 1978, Stephan wanted to see if his father would call of the event on his own, so he told his mother of his plan for both of them to stand back and watch (Reiterman 425). Eventually, when it came close to poison being rolled out, Stephan muttered, “Oh fuck,” and Jones jumped on the opportunity, claiming Stephan was too afraid to die, and using that as the redirection to call off the White Night (Reiterman 426).

In October 1978, Jones began sleeping with nineteen-year-old Shanda James (Reiterman 455), though when she wrote him a note saying she wanted to be with someone else, Jones had her put in the ECU and drugged, to the great displeasure of many of the younger men. It was the first significant moment of disillusionment for many of Stephan’s brothers, and led to Tim approaching Stephan with talks of killing Jones. Stephan responded:

“This is funny. It’s been almost ten years that I’ve been putting up with this shit. You’ve known about it for a month and you’re going nuts. You want a revolution. Let me tell you something. You know what would happen if you killed Jim Jones now?…Some of the seniors think he’s God and he’s their only hope. And you’re gonna go up there and kill Jim Jones? That won’t work. The only way you can take care of Jim Jones is to hope he dies naturally or gradually phase him out. That’s the only way you’re gonna do it. I’m sorry. There have been things I’ve wanted to do…” (Reiterman 454).

The next day, Stephan and Jones had a public confrontation about Shanda’s treatment, which lead to Stephan calling him a “fucking liar” and then both wheeling away. The young men on the basketball team took strength in seeing someone stand up to Jones, and Stephan appreciated no longer being isolated in his hatred of his father. Jones later told Tim and Johnny to put Stephan under armed surveillance, which they laughed with Stephan about. Stephan later suspected that he was being secretly drugged, and all of the guns on the compound were ordered to be turned in, though Stephan secretly kept his rifle (Reiterman 455).

When Congressman Ryan and his party came to Jonestown, Stephan and the rest of the basketball team was away in Georgetown competing against the local team. Jones urged Marceline to ask Stephan to come home early, but he and the rest of the team stayed, enjoying their time (Reiterman 474).

On the night of November 17, Stephan’s basketball team competed against the Guyana national team. They lost by 10 points, but over the radio Stephan claimed they won by 10 points instead, to the applause of the Jonestown residents (Reiterman 522).

On the morning on November 18, 1978, Stephan awoke in good spirits, with an optimistic outlook on the future. By midday though, the basketball team, which doubled as Jones’ security squad, received a message about the Jonestown defectors, and were told that Jones wanted them to enact revenge on them using knives (Reiterman 522). The team decided to go to the Pegasus hotel where the Concerned Relatives were staying and get more information from them, defying Jones’ orders (Reiterman 523).

In the radio room at the Lamaha Gardens house in Georgetown, where the basketball team was staying, Jones called Stephan over the radio and implored him to “Please, please, take care of everyone there”; to ensure that not only Tim Stoen and the enemies of the Temple dead, but that every member in San Francisco and Georgetown died as well (Reiterman 542). Stephan stalled, asking the regular radio operators if Jones had requested this and called it off before, which they affirmed. Desperate to find out more information, Stephan rode in a car with Mike Touchette and Mark Cordell to the Pegasus hotel, where the Concerned Relatives had been staying (Reiterman 543). There he argued with Tim Stoen, but didn’t gain any information on what was happening in Jonestown (Reiterman 544). When he arrived back to the Lamaha Gardens house, he found that one of Jones’ dedicated followers, Sharon Amos, had killed her children and committed suicide (Reiterman 545). Stephan went into shock, horrified by the finality of the deaths, and overwhelmed with hopelessness (Reiterman 546).

After Jonestown

Stephan was 19 years old at the time of the Jonestown massacre. After the Jonestown massacre, Stephan spent three months in a Guyanese jail as authorities tried to confirm the cause of death for Sharon Amos and her family. Stephan believed that that time in prison helped prepare him for re-entry into the world, and helped him to “mellow out” (Gorney).

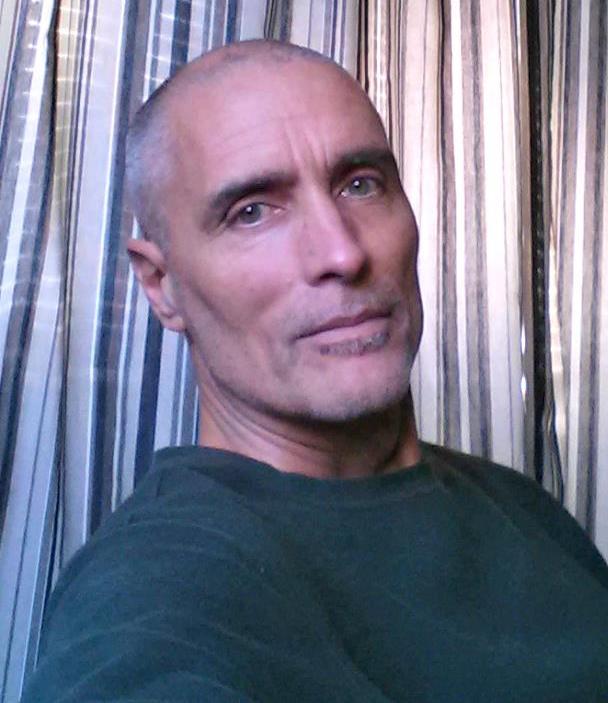

After the Jonestown massacre, Stephan moved back to San Francisco, where he stayed in close contact with other survivors of People’s Temple, including the members of the basketball team. He continued to play basketball, and was active in other ways, swimming, riding his bike, and lifting weights (Gorney). In 1991, he married Kristi Jones, and they had three children together (IMBd).

Though Stephan was public about his sorrow toward the movement and his anger toward his father, he used his platform to constantly reemphasize the humanity and sanity of the members of Peoples Temple. He claimed the media had done the late members of Peoples Temple a disservice by portraying Jones in such an overwhelmingly negative light, which made the members of Peoples Temple seem illogical for following him.

In a 2019 interview, Stephan stated, “I just wish people could understand what was attractive about him. Then they could identify and allow themselves to step into the story and understand how such a thing could happen” (Sharir).

When asked what Stephan wished people would take away from the Jonestown tragedy, he stated:

“Be aware of this message that was prevalent in the temple: ‘The end justifies the means.’ And I see that throughout society. I see it in politics, I see it in advertising, I see it in a variety of places, and I feel there’s no more pernicious or toxic belief than that. I would argue that the means justify the end, but not the other way around”.

As of December 2020, Stephan Jones has remained active in the conversation around Jonestown, taking part in interviews, appearing in documentaries, and writing reflections and articles of his own.

Gorney, C. (1983, November 7). Jonestown’s haunted son. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1983/11/07/jonestowns-haunted-son/f9369588-008b-497a-9ad3-b303dc01a8df/

IMDb. (n.d.). Stephan Jones. IMDb. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.imdb.com/name/nm2861599/

Reflections and articles by Stephan Jones. Alternative Considerations of Jonestown Peoples Temple. (n.d.). Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://jonestown.sdsu.edu/?page_id=17058

Reiterman, T., & Jacobs, J. (2008). Raven: The untold story of the rev. Jim Jones and his people.

Sharir, M. (2019, January 22). Son of anarchist: My father, Jim Jones, and what the world can still learn from him. Haaretz.com. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.haaretz.com/life/2019-01-22/ty-article-magazine/.premium/four-decades-on-jim-jones-son-tells-how-it-was-at-jonestown/0000017f-e640-d62c-a1ff-fe7b2ea00000